"THE PACIFIC PRAIRIE"

by

Frederic Clements,

John Weaver and Victor Shelford

in

Plant Ecology and Bio-Ecology

1929, 1938, 1939

Researched, Compiled and Scribed by

Robert 'Roy' Jan van de Hoek

Ballona Watershed Council & Conservancy

P.O. Box 5332, Playa del Rey, CA 90296

(818) 222-7456

robertvandehoek@earthlink.net

Š2003

This association consists of mid grasses of the bunch life form and, hence, has much the same general appearance as the mixed and true prairies. This is enhanced by the fact that it has one dominant, Stipa pulcra, which far outshadows all the others. Several other mid grasses occur with it in sufficient abundance to serve as dominants, and to the north and along the seacoast Stipa becomes secondary or is entirely lacking. The most important of these are Stipa eminens, Koeleria cristata, Poa scabrella, Melica imperfecta, Elymus sitanion, E. triticoides, with species of Danthonia, Bromus, and Festuca under moister and cooler conditions, as along the coast, in the north, and at higher levels (Fig. 265).

The native bunch-grass prairie of California has been so largely destroyed by overgrazing and fire that its reconstruction has required persistent search for relict areas. This has been so successful that it is now possible to determine its original area and composition and, in consequence, its contacts and relationships. Within the historical period, this grassland has been entirely confined to California and Lower California. Its closest affinities are with the bunch-grass community of the Palouse, with which it forms a ecotone in northern California. Today it is completely separated from the mixed prairie by the Sierra Nevada and the deserts of the southwest, but relicts of Bouteloua, Andropogon, Hilaria, and Aristida in southern California and the presence of Stipa eminens and S. speciosa in Arizona and New Mexico attest a former connection through the Mohave and Colorado deserts. This is also supported by the presence of many of its species as relicts in the mountains in and about Death Valley, and the certainty of this connection is evidenced likewise by a large number of California forbs and shrubs that still persist in the mountains of Arizona.

The native bunch grasses once occupied all of the Great Valley of California as well as the valleys and lower foothills of the Coast and cross ranges and of the Sierra Nevada. They have been more or less completely dispossessed by annual grasses introduced from Europe, as a consequence of overgrazing in a region with a long, dry season. This has resulted in making and maintaining a disclimax of annuals of such permanence as to simulate a climax, composed chiefly of Avena fatua, Bromus rigidus, B. rubens, and B. horeaceus, Hordeum maritimum, H. murinum, and H. pusillum; and Festuca myuros and F. megalura. In the case of Avena especially, the cover is so tall and dense as to have suppressed many of the perennial forbs, and the societies of the grassland are largely winter annuals, the species more numerous than in Arizona but many of them are identical. Among the most important genera are the following: Eschscholtzia, Baeria, Orthocarpus, Lupinus, Lotus, Mimulus, Gilia, Phacelia, Nemophila, Layia, Hemizonia, and Madia, while the perennials belong to Brodiaea, Calochortus, Allium Delphinium, Dodecatheon, Sisyrinchium, Pentstemon, etc.

Analysis and Conclusion

by

Robert 'Roy' Jan van de Hoek

Ballona Watershed Council & Conservancy

P.O. Box 5332, Malibu, CA 90296

(818) 222-7456

robertvandehoek@yahoo.com

Š2003

The quoted and excerpted written passage above is from the 1929 book entitled Plant Ecology. It was written as a collaborative effort by John Weaver and Frederic Clements, both of whom were scientific giants in their time in the field of ecology. Interestingly, in 1939, virtually this same passage appears in another book entitled Bio-Ecology. That book was written as a collaborative effort between Frederic Clements and Victor Shelford. Victor Shelford was a scientific giant in the field of animal ecology. Notice that Frederic Clements is a coauthor in both books. Frederic Clements studied prairies in several places in North America, including the Great Plains, the Southwest of Arizona-New Mexico, coastal California, Central Valley-California, and desert areas of California. At this time there is a renaissance occurring in California regarding the use of the term of prairie over that of grassland. It began in the 1970s in Madroņo, a publication of the California Botanical Society regarding concept of "coastal prairie" in Sonoma County. In the 1990s, two researchers of UCLA, Rudi Mattoni and Travis Longcore wrote an article in Crossosoma, a publication of Southern California Botanists, about the vanished Los Angeles Prairie. At the same time as Mattoni and Longcore, in 1995, Paula Schiffman and I, at California State University Northridge, promoted and presented an abstract of the concept of prairie in California regarding the Carrizo Plain and San Fernando Valley in southern California, at a symposium about Los Angeles Before 1900. Paula Schiffman has continued to be active in writing and research regarding the Los Angeles Prairie. In 2003, she presented to a Southern California sustainability forum at California Institute of Technology, regarding the Los Angeles Prairie. There is an article by her forthcoming in a book about Los Angeles, with a chapter on her research and philosophy regarding the Los Angeles Prairie. Meanwhile, at Madrona Marsh in Torrance and Alondra County Park in the south bay region of Los Angeles County, where there is a street ironically called Prairie Avenue, Jeanne Bellemin and I are discussing the prairie concept for Madrona Marsh Preserve and Alondra Park. At both Madrona Marsh and Alondra County Park, there is a small remnant of Los Angeles Prairie which is being restored and recovered.

Prairie - Grassland - Meadow - Vernal Pool

The American public, particularly Californians, are confused by these terms, so often used interchangeably by botanists, ecologists, scientists, and naturalists. The blame for this confusion rests primarily with botanists for not being clear in their communication to Americans and Californians. For example, the public hears the term grassland, but does not know that it also means prairie or meadow as synonyms, and even many scientists are not aware of this confused terminology. Even the term grassland is misleading because, most of the plants found in a grassland are not grasses. Most of the plants of a grassland are in the sunflower family, legume family, borage family, water-leaf family, poppy family and a few others. So why do we call it a grassland? Often, the grasses predominate and it was our eye notices first, but on closer inspection, all the flowers of a multitude of color and form begin to be noticed. Often, grasses are completely absent, and in their place, are large patches of poppies or various kinds of yellow-flowered sunflowers. So why would a poppy field of bright orange dominance be called a grassland rather then a meadow or a prairie? Why would a sea of yellow-flowered sunflowers be called a grassland, rather than a prairie or a meadow? It is not intentional to confuse the public and even scientists themselves, but our intentions and perceptions are not always in control by us. If we do not use the terminology correctly, and we call a prairie as a grassland, or a beautiful wildflower as a tarweed, rather than a tarplant or a sunflower. A developer scientist shows you a tarplant growing out of an old asphalt-tarred road and the public would perceive this as tarplant. The deception and confusion is insidious, pervasive, and subversive in its psychology. A major animal that is found in grassland is the Kangaroo Rat. However, it is not a rat according to the scientific discipline of mammalogy and studied by mammalogists. It is actually known as Dipodomys, not as Rattus of Europe. The Dipodomys is a rodent as is the beaver, porcupine, squirrel, chipmunk, rat, mouse, hamster, chinchilla, and the jerboa, but the similarities stop there. The classification of mammals depends primarily on features of the teeth (dentition), both their arrangement and morphology, of which Dipodomys is much different from other rodents. In the case of Dipodomys, additional behavioral and ecological features distinguish the Dipodomys from the other rodents. The Dipodomys has an extremely long tail, which is clother in three colors of fur (not a naked-hairless tail as in rats), and it is used as a counterweight so it can hop on its hind legs, similar to a kangaroo, and hence the first part of its vernacular name of "kangaroo." Secondly, it has large external folds of skin on the outside of the cheek that act as a pouch, which is lined with fur and if perfectly dry, with no connection to the mouth and its saliva, hence an earlier vernacular name of "pocket rat" which over time in the 1920s, became "kangaroo rat" and which mammalogists have ever since, had a challenge with teaching the public to know it as Dipodomys. Of course, the Native American peoples of California, Mexico, and the Southwestern United States, for thousands of years have had other names for these interesting creatures, long before mammalogists have called them Dipodomys, and the public has called them pocket rats and kangaroo rats. Science, scientists, natural history, and naturalists have a duty and responsibility to educate and correct their mistake of calling them rats and kangaroo. Some suggestions for the proper vernacular name to be used by the public might be "pocket rodent," "pocket mammal," or one of the variable Native American names for this remarkable animal. We use Native American names for many other mammals of the United States, such as Coyote, raccoon, porcupine, buffalo. We use positive sounding names for other mammals, such as elephant, giraffe, beaver, antelope, so let us all use a better name for this rodent of the prairies and plains of the southwestern United States.

Philip Munz and David Keck, as early as the mid-1940s, began to conceive the idea of plant communities for California, and in 1949 published their classification scheme. A careful perusal of their narrative text shows their use of the words, prairie and meadow, entwined in the Grassland community name. It is unfortunate, that they did not choose one of these two words, prairie or meadow, as they did do for "northern coastal prairie"

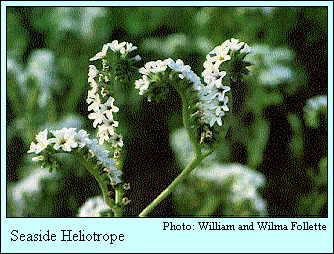

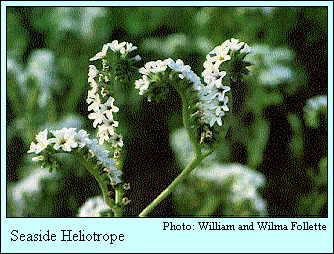

Seaside Heliotrope Anthology

Los Angeles Sunflower "Notes" by Anstruther Davidson, 1903. In Southern California Academy of Sciences Bulletin

Los Angeles Sunflower by Harvey Monroe Hall, 1907. In University of California Publications in Botany

Sacatella Creek and the Narrow-leaved Cat-tail